The Practice of Bhakti: Devotion in Indian Religious Movements

Bhakti—a term derived from the Sanskrit root bhaj, meaning “to adore” or “to worship”—has long been a foundational practice in Indian religions, particularly in Hinduism. At its core, Bhakti represents devotion to a personal deity, transcending ritualistic practices and emphasizing an intimate relationship between the devotee and the divine. The significance of Bhakti has evolved throughout history, influencing spiritual movements across India and shaping modern religious practices.

Origins and Historical Development

The origins of the Bhakti movement can be traced back to ancient Tamil hymns in the Alvar and Nayanar traditions, where devotion to gods like Vishnu and Shiva was celebrated through passionate poetry and music. However, it truly flourished between the 7th and 12th centuries CE, when it spread across northern India through the teachings of Bhakti saints like Ramanuja, Kabir, Meera Bai, and Guru Nanak.

These saints, hailing from different regions and backgrounds, emphasized a personal, emotional, and often non-ritualistic devotion to God. The Bhakti movement was revolutionary, challenging the traditional hierarchical structures of society, including the caste system and the dominance of priestly rituals. Instead, it encouraged worship of God through singing hymns, chanting mantras, and meditative prayer, making it accessible to people from all walks of life.

Philosophical Foundations of Bhakti

The Bhakti movement rejected the need for intermediaries, such as priests or scholars, to communicate with the divine. Instead, it centered around the belief that God is immanent and can be accessed directly through heartfelt devotion. Bhakti allows an individual to form a personal connection with the divine, whether it be through worship of Vishnu, Shiva, Durga, or other deities. The practice transcends rituals and encourages a direct, emotional bond with the God.

The philosophy of Bhakti emphasizes qualities like love, surrender, and humility, offering liberation (moksha) to the devotee. It stresses that devotion is not defined by outward appearances or social status, but by the inner sincerity and purity of the heart.

Bhakti as an Inclusive and Egalitarian Practice

One of the most revolutionary aspects of the Bhakti movement was its emphasis on inclusivity. Devotion, as practiced in Bhakti, did not require membership in a particular caste or adherence to rigid social norms. Bhakti saints often challenged the Brahmanical orthodoxy and welcomed followers from all social classes, including women, lower castes, and marginalized communities.

For example, Meera Bai, a Rajput princess who became one of the most famous Bhakti poets, broke with social conventions to devote herself entirely to Lord Krishna. Her songs and poems, still sung today, express deep emotional devotion and challenge the norms of her time by rejecting royal duties in favor of spiritual freedom.

Devotional Practices in the Bhakti Movement

Devotional practices in Bhakti can vary greatly, but common elements include:

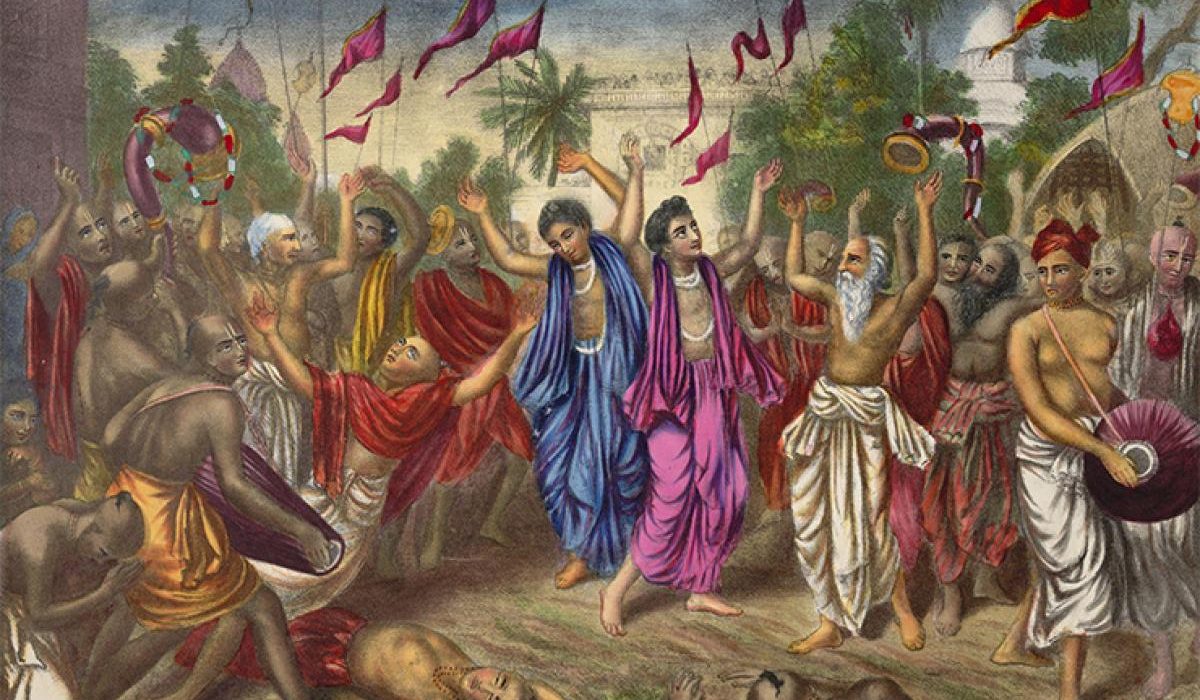

- Chanting and Singing (Kirtan): The practice of singing hymns and mantras dedicated to gods, often in the form of kirtans (devotional songs), is central to Bhakti worship. It creates a sense of community and collective devotion while allowing the devotee to focus on the divine.

- Meditation and Prayer: Bhakti often involves personal prayer, where the devotee surrenders to the divine will and seeks inner peace and guidance. Japa, or the repetition of divine names, is another common practice.

- Pilgrimages: Visits to sacred temples and pilgrimage sites associated with the deity of devotion are a significant part of Bhakti. These sites are often seen as places where the devotee can experience divine presence more intensely.

- Rituals and Offerings: Though Bhakti is less formal than traditional temple worship, many followers still engage in personal rituals and offer flowers, food, and incense to their chosen deities.

Impact on Indian Society and Culture

The influence of the Bhakti movement on Indian society was profound. It challenged caste hierarchies, promoted social justice, and led to the rise of devotional literature. Poets like Kabir, Tulsidas, Namdev, and Dnyaneshwar wrote songs and hymns that continue to inspire millions. Their works transcend regional and linguistic boundaries, forming the bedrock of the bhakti literature that is widely read and sung in India today.

Additionally, Bhakti led to the establishment of regional devotional traditions like Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism, and Sikhism, each focusing on the worship of a particular deity or understanding of the divine. These traditions encouraged the growth of spiritual communities based on shared devotion rather than social or political status.

Bhakti and Modern Hinduism

In modern Hinduism, Bhakti continues to play a central role. Temples and spiritual leaders continue to emphasize the practice of personal devotion, and the tradition has found new forms of expression through contemporary spiritual movements, including the ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness), Art of Living, and Satsang groups.

In addition to religious movements, Bhakti’s principles of emotional devotion and surrender resonate with those seeking spiritual fulfillment, transcending the boundaries of ritualistic worship.

Conclusion

The practice of Bhakti has shaped Indian spiritual traditions for over a millennium. Rooted in devotion, love, and surrender, Bhakti offers a path to experiencing the divine in a personal and intimate way. By challenging societal norms and rejecting ritualistic exclusivity, the Bhakti movement democratized spirituality, making it accessible to all. As a movement that transcends time and region, Bhakti remains an integral and transformative force in Hinduism, continuously inspiring generations to come.